From the America Studies at the University of Virginia

It is interesting to note that on Easter Sunday in 1865, the martyrdom of Abraham Lincoln began. Never had an American president been assassinated and for the murder to take place on Good Friday. provided much for clergymen around the country to preach about on this Sunday morning on what was to to become called “Black Easter.” Reacting to the shock and grief of their parishioners, religious leaders across the country put aside their scheduled Easter Sunday sermons on April 16, 1865 and set down to try and put into words the country’s reaction to the death of its leader the previous day.

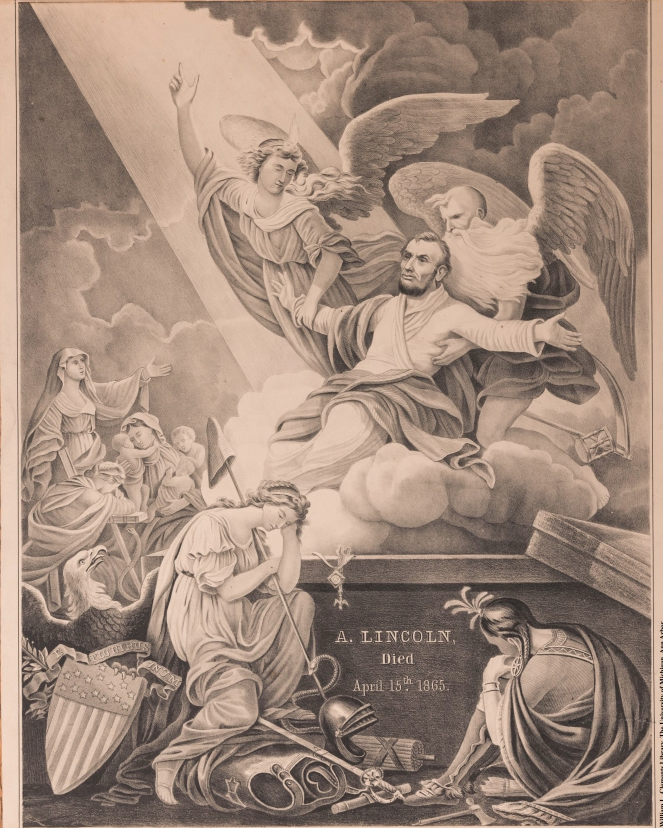

Lincoln had led the country through the darkest time, emancipated millions, struggled to reunite a broken nation and now he would pay the ultimate price for the sins of our republic. To die on such a holy day created parallels that were spoken about on that Easter morning of April 16, 1865

The Rev. Charles H. Hall of The Church of the Epiphany was like many preachers throughout the country, Hall’s 1865 Easter sermon had to be replaced at the last moment. The first and last paragraphs of Hall’s discourse, “A Mournful Easter” appear below. On the following Wednesday, Hall was one of four Washington clergy to lead Lincoln’s White House funeral.

“The words of the Burial service are the appropriate words of this troubled Easter morning. We had prepared to leave behind us the gloomier thoughts of the tomb, and decking it, as it were, with flowers and palm branches, to gaze with serene eye steadfastly on the glorious morning of the Resurrection; to forget for a while the instinctive repugnance of the human heart at the short interval of the grave; to look beyond it to the abodes of our expected reward, where tears shall be wiped from all eyes, and the disquieting fears which beset us here in the world of chances and changes would give way to eternal repose and joy. But we are called in the providence of God to look more at the sorrows than the joys that surround the Christian’s hope; to weep with those who weep rather than dwell upon the topics of our exulting hope.”

“May God give comfort to the afflicted families, whose losses will make Good Friday memorable in our national records. May He give repentance to the wretched criminals who have stained their hands, wantonly and stupidly in innocent blood, before they are called upon to meet the just punishment of their atrocities. May He give us grace to understand the seriousness and solemnity of our duties to the government over us; and as He only can, bring good out of this evil.”

In Bridgeport CT, a sermon given by the the Reverend John Falkner Blake exclaimed, “Our beloved President is dead ! Lost forevermore to us ! Lost forevermore to his country ! What is there so dear, that you would not freely have given it to have saved him for the nation. I know that there are thousands of patriots, the language of whose hearts to-day is, “Would to God I had died for thee ! ” I am sure there are those here present, who, if the Almighty God had given them the choice, would have said : “Take my child, my only child ; but, oh God, spare the head of the nation.” I know the depth of your love for our murdered President, and therefore I ask you to weep with me to-day while we consider his late relations to us as a people. As I ponder over them, they seem to roe to bear a striking analogy to those which Moses sustained to the children of Israel.”

The black community, both freed and slave, had a very distinct, if simple, picture of Lincoln. He was their “Messiah” and their savior. “They called him “Father,” as if it were part of his name…They expected him, as the Israelites did Moses.” To them Lincoln was bigger than life, and higher than any mortal man. The freedmen had “prayed he would come. They waited for him to come. And then he came!” “Like a being from heaven” he had answered their prayers and “never broke a promise to their hope.”

While this characterization of Lincoln was understandable to the white leaders who preached that Black Easter Sunday, they sought to temper it. In their enthusiasm for their “second Messiah,” the slaves and ex-slaves had “fairly blasphemed.” Many of the sermons of white leaders were interspersed with cautions against drawing parallels between biblical and contemporary figures. Some, however, found the comparisons too hard to resist and defended their sermons. “If you see a parallelism,” one reverend defended, “you cannot say the preacher makes it. If it exists, God made it.” (Another claimed that the assassination of Lincoln was “without parallel in all the annals of earthly history!” but quickly added, “excepting Him…who was the only begotten of God…and hence not to be brought into comparison with mere man. Excepting only the God-man our Savior, there has never been so sad a death!”

Despite disagreements over the degree to which explicit parallels between Lincoln and Christ could be made, both blacks and whites used the same biblical language to construct their image of Lincoln. Lincoln was often implicitly compared to Christ, quickly earning the title of “Martyr-President.” In many cases the two martrdoms were simply juxtaposed and the audience was left to draw its own conclusions. “Jesus may, by wicked hands, be crucified, but His cause lives. That is a part of God’s plan. Abraham Lincoln has fallen a martyr…But whilst our hearts are bleeding, our hopes are not crushed.”

But not all analogies were between Lincoln and Christ. The day after Lincoln’s death, a Philadelphia newspaper editorialized, “The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church. So the blood of the noble martyr to the cause of freedom will be the seed to the great blessing of this nation.” Here the central analogy was not between Christ and Lincoln, but between Christ’s church and Lincoln’s nation.

Many extended this characterization of Lincoln as Moses and applied it to the country as well. “We have passed the Red Sea and the wilderness, and have had unmistakable pledges that we shall occupy that land of Union, Liberty, and Peace which flows with milk and honey.” What the author envisioned was not the America which then existed, but rather the America promised by the potential of Lincoln’s leadership. Lincoln was “the Moses of our American Israel” who was supposedly “called of God to lead us throught the great and terrible wilderness of strife, to the promised land of unity, peace, and concord.”

Lincoln, however, was killed at the threshold of that new country as Moses was not allowed to pass into the promised land. He was “our Moses, who, under God, has lead us through the wilderness,” and who was struck down “in full view of the Promised Land, the land flowing with milk and honey.” Lincoln had stood on the precipice. He had ensured the future of his people yet been unable share in them. It was this fact, perhaps more than any other which enabled even those who had found Lincoln offensive in life to offer him such adoration and respect in death. As both underdog and tragic hero, Lincoln was destined to become an American Myth

The sermons preached on Easter Day, 1865 painted a complex and contradictory image of Abraham Lincoln. Barely 24 hours after his death, Lincoln’s memory was already being defined into two separate aspects. He was both the representative man — common and average in every way, and the exemplary man — larger and stronger and wiser than any mere mortal. As one pastor put it, “great and distinguished persons” become, through association of their characters to those institutions and communities to which they were a part, “representative men.” And where “such arise, they are especially the property of the individuals whom they represent; and generally of the country producing them.” Lincoln, as a symbolic figure, was claimed not only as representative of the American people who had followed him during his life, but also of the character of the country as a whole.

His beginnings were not only of the humblest sort, but also of the most uniquely American. His boyhood was placed firmly within the popular image of the American Frontier. Descriptions of Lincoln’s youth are interspersed with the hyperbole of the West’s tradition of tall tales. A scholarly Paul Bunyun, Lincoln grew to an “unusual height” and “could outrun, outlift, outwrestle” any of his companions and “chop faster, split more rails in a day, carry a heavier log…or excel the neighborhood champion in any feat of frontier athletics.” His childhood, as seen through campaign biographies and newspaper stories, was the stuff of American legend.

After his death the association of Lincoln’s character with American tradition grew. The clergy, alongside their biblical images of Moses and martyrdom, also invoked the images of the founding fathers. In addition to placing the Emancipation Proclamation “with the Declaration of Independence,” these sermons also established a link between Lincoln and the nation’s first president. “In all future history his name will stand beside that of Washington. If he was the father of his country, under God, Abraham Lincoln was its savior.”

To many the timing of Lincoln’s death underlined, with its injustice, the accomplishments of his life. “The great and glorious Washington was re-elected President of the United States in the time of peace. The second Father of his Country, Lincoln, in the time of war…Washington died in old age, in peace, his work completed, his service ended. Lincoln died in the full flush and prime of life” at the climax of the Civil War.

If the presidency was “the highest [position] which has ever been filled by man,” then Lincoln’s term in office was the most important period during which the position was filled. Yet even more important was the popular characterization of Lincoln as a “Father” to the country. “When God raises up any man, who, in character, ability, and achievement, is accomplishing great good, his removal is a sore calamity to the people.” More than the leader of a “Heaven-blessed Government,” however, Lincoln was seen as a role model for all Americans.

Lincoln’s “tall, manly form” was “accessible” to the common man and the loss of that model left a rend in the fabric of American consciousness. It is perhaps for that reason that his memory has lived on in American iconography. When the sermons of April 16, 1865 asked the American people “pledge [themselves] not only to the affectionate memory of our MARTYR but to the imitation of his character and the perpetuation of his principles” a place was created for Lincoln in the American mind which existed ever since.

Reverend Henry Bellows of New York City informed his congregation that “Heaven rejoices this Easter morning in the resurrection of our lost leader . . . dying on the anniversary of our Lord’s great sacrifice, a mighty sacrifice himself for the sins of a whole people.” In Philadelphia, minister Phillips Brooks assured his flock that, “If there were one day on which one could rejoice to echo the martyrdom of Christ, it would be that on which the martyrdom was perfected.”